1918 Pandemic in Meeteetse and Park County: Part I Symptoms, Personal Protective Equipment, and Medicine

By Alex Deselms, Director of Collections

Depiction of clothing worn by a plague doctor courtesy of I. Columbina, ad vivum delineavit. Paulus Fürst Excudt. – Internet Archive’s copy of Eugen Holländer,Die Karikatur und Satire in der Medizin: Medico-Kunsthistorische Studie von Professor Dr. Eugen Holländer, 2nd edn (Stuttgart:Ferdinand Enke, 1921), fig. 79 (p. 171)., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15677032

People have been combating disease by wearing masks and face coverings for centuries. Unfortunately, we don’t have a European doctor’s plague mask in the collection for comparison (these curved beak-like masks were only in use during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (1600s and 1700s)). But we can trace mask use and other precautions in the last pandemic – the 1918 influenza, sometimes called the Spanish flu. There have been numerous articles discussing this previous pandemic over the last year at state and national levels, but what did it look like in Meeteetse specifically? Or Park County generally? We don’t have archival records to review, but we do have old newspapers available online through the Wyoming State Archives to study.

Of 60 cases in Cody by October 18, 1918, there were four deaths, including Mr. and Mrs. Garlow of the Irma hotel (William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody’s daughter and son-in-law). A week later, there were three more deaths. By the end of November, Powell was up to a dozen cases; by December, Powell had had 187 cases and a dozen deaths.

On December 6, the Meeteetse News reported many new cases in and around Meeteetse and wrote that a “look of anxiety now appears on the faces of many who heretofore gave it but little thought.” (Sound familiar? COVID didn’t seem like a big deal to many of us in February 2020, but it was definitely on our minds in March.) There were six new cases in the previous two days before the paper came out and those at the Pitchfork Ranch were some of the most severely affected, most being under a doctor’s care.

Bottle of Allen’s Cough Balsam medicine circa 1919 in the Meeteetse Museums’ Collections. You can see a full bottle at the National Museum of American History here: https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_209225

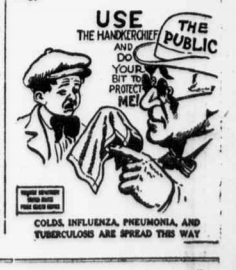

Another article in the Meeteetse News (a supplemental issue on December 20) reminded readers to go home if they felt ill to heal and to prevent spreading the Spanish flu to others since even a mild case in one person could spread, causing severe illness in someone else. Reminders to cover your cough and sneeze (and stay away from people who don’t) were published in this article. Tips included staying away from crowded and stuffy places, keeping houses and businesses well aired, and just generally keeping to places where one could “breathe as much pure air as possible.” The article ends with the catchy slogan “Cover up each cough and sneeze / If you don’t you’ll spread disease.” Besides catchy slogans, pictures, drawings, and cartoons can be used to illustrate and reinforce important points. A cartoon was published or reprinted showing an older man (“the public”) using a handkerchief near a young boy with the caption “Use the handkerchief and do your bit to protect me.” (December 27, p.5) This is similar to the messages we’ve seen during COVID about how wearing masks helps us protect our neighbors and, in turn, our neighbors protect us.

Cartoon published in the Meeteetse News’ December 27, 1918 issue on page 5.

A description of symptoms is featured in the October 9, 1918, issue of the Northern Wyoming Herald and begins by discussing general cold, cough, fever, pain, and depression symptoms, adding that for influenza, these were more severe and spread more rapidly, while also appearing outside of just the winter months. Further, a patient would likely feel sick rather suddenly with weakness, pains in the eyes, ears, head or back, while also feeling sore all over. Dizziness and vomiting could occur. Patients may complain of chills while also having a fever of 100 to 104, with a potentially slow pulse.

“In addition to the appearance and the symptoms as already described, examination of the patient’s blood may aid the physician in recognizing the ‘Spanish influenza’ for it has been found that in this disease the number of white corpuscles shows little or no increase above the normal. It is possible that the laboratory investigations now being made through the National Research Counell [sic] and the United States Hygienic Laboratory will furnish a more certain way in which individual cases of this disease ea[—] recognized.”

(Anyone else having a sense of déjà vu with how additional COVID testing became available to recognize more cases and symptoms?)

Later, the article in the Herald details caring for patients, including not blindly taking the remedies from patent-medicine manufacturers and wearing personal protections as well as taking care of oneself to be the strongest one could be to fight off any infections. Especially for those assisting non-family members, “it is advisable that such attendant wear a wrapper, apron, or gown over the ordinary house clothes while in the sick room, and slip this off when leaving to look after others. Nurses and attendants will do well to guard against breathing in dangerous disease germs by wearing a simple fold of gauze or mask while near the patient.” (And the need for masks as a health, safety, and prevention measure continues to be seen.)

Similar to the increase of Personal Protective Equipment production and sewing sessions over the past year, the 1918 influenza had its share of volunteers creating large numbers of masks and other medical gear. “The ladies of the gauze department have been working at the court house every afternoon, making and distributing the gauze masks to be worn during the epedemic [sic] of influenza. Two hundred were made in one afternoon.”

The above report (on the Red Cross in the Park County Enterprise on October 30, 1918) continued to discuss volunteerism. Cody teachers volunteered as nurses and “have gone from one case to another helping in a manner that cannot be estimated.” The chairmen H.B. Robertson was praised for the Red Cross’ efforts even as the article cautioned that those needing help should be looked after (when possible) by members of their own family or neighborhood since “Illness is so general that every quarter of town has its families who need cooked food and such attentions as filling of coal baskets, caring for children, lending bed linen, etc.” The article even tried to encourage competitive volunteerism: “Can any one break Mrs. Slade’s record of six pies, six puddings and six pans of gingerbread, all in one day?” An announcement on the front page of the Park County Enterprise earlier on October 9, 1918, called for “patriotic women” of Cody to assist doctors and nurses as part of the Cody chapter of the Red Cross.

Much like during COVID, a focus was on finding vaccine and medicinal solutions to slow or stop the pandemic. On January 22, 1919, the Park County Enterprise reported an article (or possibly an editorial) by B.C. Brooke, M.D. of Helena that the influenza vaccines were effective in helping prevent and limit deaths. Dr. Brooke did note that while physicians did not know for sure how long the vaccine would last or prevent reinfection, he was of the opinion that any reputable vaccine should be used. Being on page 4, you wonder how many people read his column.

On the other hand, an article from later that year in the November 19, 1919, Park County Enterprise described the U.S. laboratory director as skeptical of any serum or vaccines actually doing much to prevent the spread. It was reprinted on May 12, 1920. Earlier, in October 1918, it was announced in the Park County Enterprise that a serum was proving effective against the pneumonia which often followed influenza cases. (During the influenza pandemic, it was primarily the pneumonia that occurred after influenza that caused death.)

An article from the Thermopolis Independent (reprinted in the January 3, 1919, Meeteetse News) showed how large cities throughout the country were requiring larger orders of coffins…impacting the ability of local undertakers (like Thermopolis’ P.H. Knight) to order the caskets from their normal places. In this case, Knight had to switch his supplier from Denver to Minneapolis as well as commission local makers to manufacture caskets.

Vick’s VapoRub advertisement and public thank you note printed in the Meeteetse News pg. 7 on March 21, 1919.

Advertisements tailored their messages to use the influenza pandemic (and corresponding fears and worries) to promote their products. In March 1919, an ad for Cascara Quinine in the Meeteetse News reminds readers to get plenty of fresh air and exercise, but at the first sign of a cold, to take their medication. Another later March article advert for Vick’s VapoRub thanked pharmacists for being so dedicated to staying open to help (and to all those who purchased VapoRub as they distributed 13 million jars since October). They continued through February 27, 1920, when the Powell Tribune advertised various Watkins remedies (including Watkins Cold and Grip Tablets, Watkins Cascara-Senna Tablets, and Watkins Stock Tonic) to help keep an individual in good health to prevent influenza.

Does anyone have an account of the 1918 pandemic in Meeteetse? Or photos of that time? We’d love to see or hear them!