“Buffalo Bill” Cody and the Transylvanian: Connections Between the American West and Count Dracula

By Elizabeth M. Foss, Public Outreach and Engagement Director

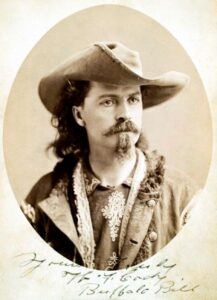

Vampires and cowboys are not often talked about in the same breath, though these two figures loom large in popular media. As distant as they may seem, vampires and cowboys are uniquely tied together in the hit novel that gave birth to our modern idea of the vampire: Bram Stoker’s Dracula. “Buffalo Bill” Cody’s Wild West helped shape Dracula in unique ways, which we will explore in this post. Irish-English author Bram Stoker published the novel Dracula in 1897, kicking off an international fascination with vampires as suave aristocratic villains rather than the mindless revenant they traditionally were thought of in Eastern and Slavic folklore. Dracula has been in print since 1900, speaking to the story’s longevity. Stoker personally met William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody in 1887 when Cody was in London on the European tour of his Wild West show, and corresponded with Cody before this date. Stoker met Cody through his acting connections; he worked for and was friends with English actor Henry Irving. By this time, Buffalo Bill Cody was an international celebrity for his depictions of frontier life in the American West.

Author Bram Stoker, c. 1906.

Historian Louis S. Warren, author of “Buffalo Bill’s America: William Cody and the Wild West show” argues that Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West show was an important inspiration for Dracula. Namely, Warren argues that both Dracula and the Wild West show are about frontier encounters, and that “the frontiers of racial encounter were invested with the possibility of degeneration and the necessity of race war.”1 Keep in mind that in this period, race was more than skin color, encompassing ethnicity and culture as well as physical attributes. In Dracula, the frontier was Eastern Europe, which Stoker presented as the “wildest and least known portions of Europe,” even calling Dracula’s home of Transylvania “the frontier.”2 The racial encounter in Dracula was between the English and various ethnic enclaves in the Carpathian Mountains, with the undead vampire Dracula as the pinnacle example. The threat of degeneration came from Dracula leaving Transylvania for England to prey on the English, leading to the necessity of conflict that Warren highlights. In the real-world example expressed in Cody’s Wild West show, the frontier encounter was with Native Americans, and the conflicts Warren references were the various Indian Wars of the nineteenth centry across the American West.

England was fascinated with Buffalo Bill in the later half of the 1800’s, but there was an edge of fear to that interest; there was a general perception that as the United States rose to international prominence, England was on the decline as a world power. In her Master’s thesis “The Colonization of Quincey Morris: The American Other in Bram Stoker’s Dracula,” Jessica Wojtysiak states that “[l]ate Victorian literature is often characterized by anxiety over the gradual erosion of British cultural hegemony, particularly the view that the English nation was suffering from a state of irreversible decline”3 Consider how the United States asserted itself as sole steward of the Western Hemisphere with the Monroe Doctrine in 1821; though this doctrine was not necessarily enforceable when President Monroe gave this statement to Congress, it gained legitimacy as the United States grew in military power during the later half of the 1800’s. During his presidency, Theodore Roosevelt built up the navy to actually enforce the Monroe doctrine, and his added corollary asserted the U.S. right to intervene in South American affairs. The U.S. was steering itself more actively into the world political sphere, which had a hand in creating an English anxiety of losing hegemony. In his show, Buffalo Bill Cody presented American exceptionalism through storytelling and physical acts of skill framed as necessary to survive on the frontier, thus becoming another source of anxiety over U.S. prominence. In Dracula, this anxiety of English decline manifests in part as the undead Count Dracula attempting to prey on English people and take English land, in effect an act of reverse colonization.

William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, c. 1875.

One especially strong parallel can be drawn between the persona Buffalo Bill Cody presented in his Wild West show and the fictional character Dracula; both represent a frontier, or a peripheral land where “civilization and savagery meet.”4 Both are, in Stoker’s narrative, people and lands that the British must conquer and civilize to prevent them from harming the Empire. Though superficially they differ in surface level character traits, with Buffalo Bill as American hero and showman, the Count as villain bent on the destruction of innocence, the frontier parallel stands. Warren suggests another anxiety present in Dracula: that the frontier acts as a “place of racial monstrosity,” where the Anglo-Saxon pioneer transforms into a threat to the metropole, or parent state of a colony.5 In Dracula, the single American character expresses the danger Warren references here perfectly. Quincey Morris, a Texan cowboy, becomes a threat to the English protagonists when he continually messes up the hunt for Dracula; in fact, Stoker writes that an error by Morris lets Dracula escape England for Transylvania with an English woman under his sway.

Cody’s influence on the narrative can be easily seen in the character Quincey Morris. Quincey is one of the many suitors to the character Lucy Westenra, Dracula’s first victim in England. Stoker describes Quincey as a cowboy from Texas who can travel in civilized English circles, but not completely fit in. Take his marriage proposal to Lucy for instance, where he speaks in slang: “Miss Lucy, I know I ain’t good enough to regulate the fixin’s of your little shoes, but I guess if you wait till you find a man that is you will go join them seven young women with the lamps when you quit. Won’t you just hitch up alongside of me and let us go down the long road together, driving in double harness?”6 He talks differently, he has past experience with a vampire threat (but in his case a vampire bat which drained his horse in the Pampas of South America), and he is more quick to violent action than his English counterparts.7 Quincey is experienced with the frontier, making him an asset when facing Dracula, but at the same time, that closeness to the frontier environment marks him as a threat to the English norm. Cody’s entire performance persona depended on his frontier experience, as with the other performers in his troup, illustrating how he likely inspired the character of Quincey Morris in Dracula.

There have been numerous play and film adaptations of Dracula. Pictured here is Béla Lugosi as Dracula in the 1931 Universal Studios film.

Continuing this look at the cowboy character, Quincey can be viewed as an expression of English anxiety over the U.S. emerging as a world power. Wojtysiak describes Quincey as “both invader and friend” for his shared characteristics with Dracula, such as his wealth, “attractiveness, reticence, and predilection for decisive and often violent action.”8 To illustrate Quincey’s reticence, in Dracula one character describes the cowboy thus: “What a fine fellow is Quincey! I believe in my heart of hearts that he suffered as much about Lucy’s death as any of us; but he bore himself through it like a moral Viking. If America can go on breeding men like that, she will be a power in the world indeed.”9 Though this seems to be praising his moral character, Quincey is presented as not having the correct response to Lucy’s death compared to what the English characters expressed. Quincey is singled out in this example as different from the other characters, and explicitly as a representation of the United States. With his similarities to Dracula, Quincey, and by extension the U.S. which he represents, are framed as a threat.

Reproduced cover of the first 1897 printing of Dracula.

Following the line of though that Quincey is a parallel to Dracula, Quincey emerges as a more subtle threat than Dracula because he can travel in English social circles. For example, he successfully drew Lucy’s interest, more so than her third suitor, Dr. John Seward. When Quincey proposes, Lucy is moved to tears when she had to turn him down because she loved another, and Stoker spends quite some time describing their reconciliation, with Lucy even giving Quincey a kiss before he left. With Seward’s proposal, Lucy is also moved to tears, but does not express any thought of actually accepting his offer though he is described as a better social match for Lucy due to his high birth. Quincey moves within these social circles, finding footing due to his wealth, cunning, attractiveness and charm. Though Quincey can move within the social circle in Dracula, he is never fully accepted, because he is a bridge between the civilized and uncivilized world. Of note, Quincey is the only protagonist fighting Dracula to actually die. All the English characters and the Danish Van Helsing survive their encounters with Dracula. Quincey Morris dies to save Mina Harker, the English woman under Dracula’s sway, and in this frame he furthers the English imperial authority mindset. The story ends with Mina Harker naming her first born after Quincey, perhaps suggesting how Stoker envisioned England again rising to international power: by embodying America’s strengths while reshaping them into a more English mold.

Bram Stoker saw in Buffalo Bill Cody and his Wild West show an American West fraught with opportunity and threat of the uncivilized. Stoker embodied this interpretation of the West in Dracula, presenting Eastern Europe as a frontier that bridged Europe and the East which could present threats to a metropole such as England unless those lands were conquered and civilized by the British Empire. At the same time, Stoker encapsulates an English fear of American preeminence in the world, tying that rise to world power as a sign that the British Empire was declining. This is presented as cowboy Quincey Morris, a parallel to Dracula, enmeshing himself in the English character’s social circle and causing them harm. Buffalo Bill Cody, as a representation of the American West and the frontier environment of racial encounter, served as an inspiration for the iconic Dracula that still holds world attention today.

Footnotes:

1: Louis S. Warren, “Buffalo Bill Meets Dracula: William F. Cody, Bram Stoker, and the Frontiers of Racial Decay,” History Cooperative, accessed 10 October 2023, https://historycooperative.org/buffalo-bill-meets-dracula-william-f-cody-bram-stoker-and-the-frontiers-of-racial-decay/.

2: Bram Stoker, Dracula (New York: Signet Classics, 1978), 6-7.

3: Jessica Wojtysiak, “The Colonization of Quincey Morris: The American Other in Bram Stoker’s Dracula” (California State University 2015), 2.

4: Frederick Jackson Turner, “Significance of the Frontier in American History” (1893) American Yawp Reader, https://www.americanyawp.com/reader/17-conquering-the-west/frederick-jackson-turner-significance-of-the-frontier-in-american-history-1893/.

5: Louis S. Warren, “Buffalo Bill Meets Dracula.”

6: Bram Stoker, Dracula, 68.

7: Bram Stoker, Dracula, 169.

8: Jessica Wojtysiak, “The Colonization of Quincey Morris,” 3.

9: Stoker, Dracula, 193-194.

10: Stoker, Dracula, 69.