Valentine’s Day

By Alexandra Deselms, Interim Director

Valentine’s Day: A History

Valentine’s Day brings memories of school parties with cards and candy exchanged and/or fancy date nights. The Museum recently found some historic Valentine cards in our collections and thought we’d look into them, to see how they fit into the history of Valentine’s Day and Valentine cards.

Before Christianity, ancient Rome celebrated the fertility festival of Lupercalia on February 13-15 (for more information, check out the list of references and resources below). In the 5th Century Common Era, the pope authorized the feast day of St. Valentine to reclaim the holiday and Christianize it. Two of the at least three St. Valentines had their feast day on February 14 so the addition of celebrations was relatively easy to use to replace the ancient Roman holiday. The St. Valentine that has the most relevance to the holiday as we’ve come to know it is Valentine of Rome, who was jailed and executed for marrying soldiers (the emperor had ordered soldiers to be single in the belief that they would make better soldiers that way); he either fell in love with or healed (or both) his jailor’s daughter and left her a note signed “your Valentine.”

The earliest known mention of the holiday was in Geoffrey Chaucer’s poem the “Parlement of Foules” in the fourteenth century. The first surviving written greeting was a letter on Valentine’s Day from the Duke of Orleans to his wife while imprisoned in the Tower of London after the 1415 Battle of Agincourt. This letter is now in the collection of the British Library, which also has the first surviving Valentine’s card written in English, dating from 1477. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, court celebrations and parties began to occur on the holiday. Around the same time, that most famous Valentine’s poem began to appear in nursery rhymes – different versions of “roses are red.”

The first Valentine cards and gifts that we would recognize as such were sent in the eighteenth century. These first cards were handmade, consisting of paper decorated with romantic symbols like flowers and love knots and often including puzzles or lines of poetry. Books appeared to give guidance on appropriate words and images if one couldn’t think of anything on one’s own. The created cards were slipped under the recipient’s door or tied to their door-knocker. The first pre-printed cards appeared in Georgian Britain, with the oldest surviving from 1797. Little gifts had sometimes been exchanged before, but giving flowers was introduced during this period and the flower language (the meaning of different flowers) became popular.

Valentine’s Day came into its own in the nineteenth century under the Victorians. With industrialization, cards (such as machine-printed lithographs) were able to be cheaply and easily mass produced. With the advent of the Uniform Penny Post in 1840 in Britain, it became possible to send cards inexpensively.

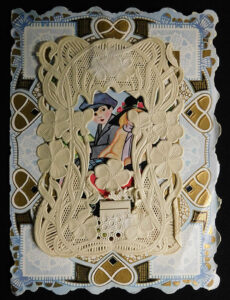

These mass produced cards had a huge array of designs, verses and sentiments. They tended to feature elaborate paper lacework, embossing, and other intricate designs; typical imagery included flowers, love knots, and Cupids along with some hearts (but not red). Layers and windows revealed images from cut paper, and the intricate images were in full color. Of course, the more expensive the card, the more elaborate it was so the recipient could usually tell approximately how much the sender had (or hadn’t) spent on the card. These ready-made cards were an easy (and acceptable) way to express emotions in a time when direct expression of one’s feelings was discouraged. Mostly, men sent these cards to women or women sent them to their female friends, as it was too forward to send cards from women to men during this time of strict propriety.

Like today, some Valentines’ cards were humorous – but the Victorians took it to an extreme with the “Vinegar Valentines” that were designed to insult. Insults tended to center on a man’s profession, a woman’s appearance, and women’s suffrage; lower class minorities like the Irish and African Americans were targeted in the United States. The origins of these cards were the 1830s or 1840s; by the end of the century, they had largely fallen out of favor due to the extreme reactions and regular letters of complaint. These cards were often sent anonymously, either to fend off an unwanted suitor, an enemy, for those not on good terms, or perhaps to point out “moral failings” (possibly in the hope of prompting change, but mostly just to chide and wound). There were few repercussions due to their anonymous sending; even worse, the cards were often sent “cash on delivery” so that the recipient had to pay a penny to read an insulting card.

The earliest (handmade) cards in America may also have been exchanged in the early 1700s and hand delivered. During the mid-nineteenth century, cards traveled from Britain and gained popularity in America. This was particularly true after the Civil War, when trauma from the war led to a rise in sentimentality. Advanced American technology also meant more elaborate cards could be produced cheaply. By the early 1900s, marketing campaigns had added the sales and gifting of jewelry, flowers, and perfumes to the holiday. The first Hallmark Valentine’s card was sold in 1913. Braille valentines (with embossed figures of birds and hearts accompanying braille verses) and die-cut shaped valentines also appeared around the turn of the century.

The “Mother of American Valentines” is Esther Howland from Massachusetts. She received a valentine from a friend in Britain in the mid-nineteenth century; as her father had a stationary store, she could cheaply and easily order papers and illustrations from Europe to use. With girls working upstairs in her father’s house in a production line style ‘factory,’ she and her workers created elaborate creations with real lace, ribbons, and colorful pictures known as “scrap” before she sold the business in 1881.

As the twentieth century progressed, the holiday became more and more commercialized. Chocolates and lingerie were added to the gifts exchanged. Family members began exchanging cards, not just friends and romantic partners. The early twentieth century also saw the beginning of school children trading cards in the classroom. While the twenty-first century has added ecards and texts, putting pen to paper for loved ones and lovers is still popular: “It is this last activity that encapsulates the modern spirit of Valentine’s Day – the profession of love and admiration through the written word.” (“History of Writing Valentine’s Day Cards,” Pen.com) Indeed, the Greeting Card Association estimates that 145 million Valentine’s Day cards are sent each year, making it the second largest card-sending holiday after Christmas.

Meeteetse Museums’ Collection

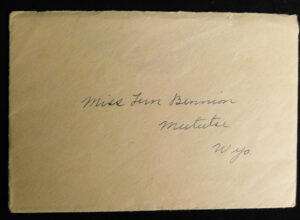

An envelope containing a Valentine’s Card address to Fern Bennion.

Our collection of Valentine cards comes from Fern Bennion Peoples in the early twentieth century. Most people think of greeting cards from Hallmark or American Greetings. But at the turn of the century and up to World War II, the big player was the Whitney Made valentines, along with other companies like Carrington. Our valentines are from both Whitney and Carrington (or are of unknown manufacturing).

“Whitney Made” card from the Meeteetse Museums’ collection.

George C. Whitney helped his brother and sister-in-law with their sideline Valentine business (their primary business was a stationary store). After his brother’s death, George bought out competitors like Howland and A.J. Fisher’s comic (vinegar) Valentines (although George didn’t use any plates from the last one as he didn’t like “using love’s gifts as a medium for ridicule”). (“Whitney-Made,” Worcester Historical Museum blog) His Valentines often featured hearts or were heart-shaped just as when he added Christmas cards, they often depicted or were in the shape of Christmas trees. Whitney became the biggest producer of American valentines (a 1915 magazine believed 90% of valentines came from Worcester and Whitney) and added other holidays like Halloween, New Year’s, and Easter as well as calendars, books and booklets.

George died in 1915 and his son Warren and grandson George took over. The 1920s saw more serious competition with growing companies like Carrington, Rust Craft, Gibson, Buzza, Hall Brothers, and American Greetings. This led to a small change in the market – more cards were sold to young school children and the price became cheaper overall; styles, however, remained fairly similar from the 1920s to the 1930s and even to the 1940s. “By the 1930s, the delicate, applied bits of paper and lace had completely disappeared from factory-made cards, replaced with relatively inexpensive, mass-produced valentines marked ‘Whitney Made / Worcester, Mass.’ on the backs.” (“Valentines,” Worcester Historical Museum Digital Exhibit) The Whitney company closed in 1942 because it couldn’t withstand the paper shortage of World War II and couldn’t repurpose machinery for the war effort.

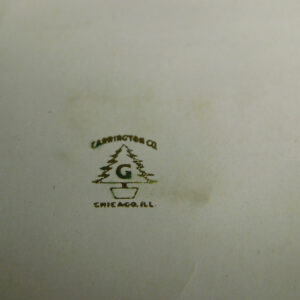

An example of the lettering system on Carrington Company cards from the Meeteetse Museums’ collection.

Less is known about the Carrington Company based in Chicago. They were started before 1917 and bought out Whitney in 1942. They continued to create cards despite shortages until they closed in 1955. The Carrington logo is a tree with a letter inside, possibly to indicate price. Most letters are A, H, C, and E. Our Carrington card has the letter G.

Fern Bennion Peoples was born on January 5, 1909 to parents Edgar and Effie Bennion, who were living in Canada at the time. The family returned to the Meeteetse area shortly after Fern’s birth, living in Burlington and then along the Wood River. In high school, she participated in sports and plays with schoolmates Lilias Nelson, Harold Thayer, Billie Thayer, Bill Wilson, Ethel Larsen, and Ruth Scovel. She married Evart Peoples on June 18, 1927 in Cody and they had two children. She died on May 26, 1993 in New Mexico; after her death, the Museum accepted some donations from her estate.

With a couple exceptions, the senders signed their name (and addressed it to Fern) on the back of the card and not the inside. Perhaps people liked to hang or frame the insides and didn’t want their name on display. No matter where they signed, having the names enabled us to check reference files, yearbooks, and Ancestry.com to put the pieces together on the likely senders.

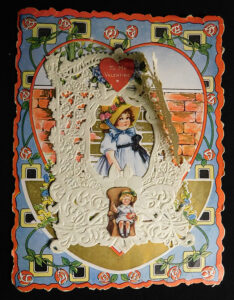

This lace-framed Valentine from Fern Bennion’s grandmother, Anna French Moore, is one of the Whitney Made cards in the Museums’ collection.

One card is addressed to Fern “From Grandma Moore.” Grandma Moore would be Effie Moore Bennion’s mother, Anna French Moore. Born in March 1861 in Ohio, she died in November 1935 in Cody. The family came to Meeteetse around 1898 and Effie married Edgar Bennion in April 1900. Fern could have received the card anytime between 1910 and Anna’s death in 1935, although it is likely to be the late 1910s or early 1920s. This card is one of the Whitney Made cards in the collection and features paper lace on the cover around a young girl in a hat; another girl sits sewing in a chair below the lace, and inside the card is a little verse and illustration.

Another card is “To Fern Bennion” from “Ethel Larsen”. Ethel Larsen was a schoolmate who was a year behind Fern in school. During Ethel’s sophomore year in 1927 (and Fern’s junior year), they played together on the girls’ basketball team. They also served on “The Spur” yearbook staff together. The card from Ethel has two children with balloons on the cover, a verse inside, and is also a Whitney Made card. It was likely given to Fern in the 1920s.

Card from HHT, likely Harold Thayer.

Fern received one card from “HHT” and another from “Harold”. Both are likely Harold H. Thayer, who was a classmate and participated in plays with her. Harold Thayer was a sophomore with Fern in 1926 but “joined another class” to become a senior in 1927 (while Fern was a junior). Harold gave the valedictory speech at graduation (a copy of the speech is in the 1927 yearbook). Harold and Fern were sophomore class president and vice president (respectively) and served on the yearbook staff together.

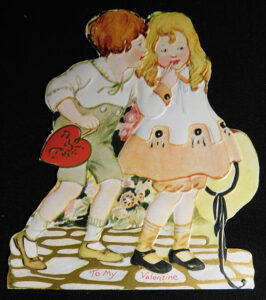

The HHT card is just a simple little business-card type with a small verse and two children holding hands. It came in an envelope addressed to “Miss Fern Bennion / Meeteetse, Wyo.” The Harold card has a boy and girl whispering together and is cut in the silhouette of their torsos; it too is a front and back only and the only manufacturing mark says “Made in the USA.” These would both likely have been from the 1920s.

Fern also received a card from a “Billie” and a “B”. One or both could be from Bill Wilson, who Fern was in plays with, or Billie (Billy) Thayer. Thayer was born in Dec 1908 in Fenton, Wyoming and was a sophomore with Fern in 1926; like his cousin Harold, Billie “joined another class” to become a senior. He went on to earn a degree in mineralogy from UC Berkeley and started an X-ray company in Tulsa for use in large pipeline installations. The “B” card could also be from Fern’s brother Boyd.

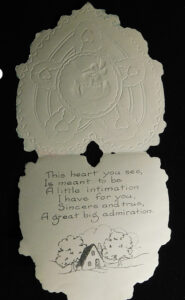

Inside of the card from “B” to Fern. This card, like many in the collection, was signed on the back.

The B card is a card in the shape of a heart (gold-colored) with a puppy in the center, which opens to a verse; it is also a Whitney Made valentine. The Billie valentine has a boy chasing a girl and is cut in the silhouette of their torsos with a verse on the front; it only says “Made in USA” for its manufacturing. Both cards are likely from the 1920s, or late 1910s.

Valentine from Lilias Nelson Linton to Fern.

One card Fern received is from “Lilias.” Lilias Nelson Linton was in plays and school with Fern (as well as playing basketball together) before marrying Angus Linton. Lilias gave the “Class Memorial” and senior farewell on May 14, 1926 and helped create the new Spur yearbook while serving as senior class president when Fern was a sophomore. Her card is a stand-up card with a boy falling over a heart (with a verse) while a girl stands behind. There is no manufacturer’s mark, but the card was likely given in the 1920s.

Valentine from Ruth Scovel.

Another card received by Fern is from “Ruth”. Ruth is likely Fern’s schoolmate Ruth Scovel, who participated in theater and basketball with Fern. She was born in May 1910 near Meeteetse and was a year behind Fern in school, serving as freshman class vice president and sophomore class president. She was the 1929 valedictorian at graduation before marrying John Hamilton Tyson in Cody and having two sons with him. After a divorce, she married Harold Shoemaker from Greybull in 1939 and had a daughter with him. Following his death in the mid-1940s, she later married an old Meeteetse friend, Merl Hovey. The card from Ruth has paper lace on the cover with a verse inside. Interestingly, it has both Whitney Made and Carrington Co. as the manufacturer on the back; however, when Carrington acquired Whitney in the 1940s, Fern would have already been Fern Peoples, not Bennion, after her marriage to Evart in 1927. When this card would have been sent thus remains a mystery.

Valentine from Helen E. Peterson to Miss Fern Bennion.

The only dated valentine card Fern received was from “Helen E. Peterson” and is dated “Feb. 14, 1918.” Previous research in our reference files shows that Helen was a teacher in the area: at Dick Creek in 1919-1920; at Sunshine 1920-1922; and 3rd and 4th grades at Meeteetse in 1922-1923. Given the date, Helen must have been in the area by early 1918 (before she began teaching), unless she had previously known the family and mailed the card without the envelope being saved. This is another Whitney Made card, with gold gilt around two hugging children.

We hope you enjoyed this lesson about early 20th century Valentines in the Meeteetse area. The cards will be cataloged and up on our online collections site soon for you to enjoy!

Resources / Further Reading

- Ancestry.com

- “Be My Valentine,” Smithsonian Online Exhibit, https://www.si.edu/spotlight/valentines

- “History of Valentine’s Day” by History.com Editors, original Dec 22, 2009 – updated Jan 24, 2022; accessed Feb 1, 2022. www.history.com/topics/valentines-day/history-of-valentines-day-2

- “The History of Valentine’s Day Cards,” www.scrapbook.com/articles/valentine-history

- “The history of Valentine’s Day cards,” Beryl Jones, www.homeandantiques.com/antiques/collecting-guides-antiques/the-history-of-valentines-day-cards/

- “The History of the Valentines Day Card,” Meghan, Feb 14, 2017. History Cooperative, accessed Jan 31, 2022. https://historycooperative.org/history-valentines-day-card/

- “A history of Valentine’s Day celebrations – from fertility festivals to the first cards” Feb 10, 2021, Dr. Anna Maria Barry (cultural Historian) (first published HistoryExtra in 2015); https://www.historyextra.com/period/modern/when-was-valentines-day-first-celebrated-cards-history-saint-valentine/#:~:text=

- “The History of Writing Valentine’s Day Cards,” www.pens.com/blog/the-history-of-writing-valentines-day-cards/

- “How the Modern Valentine’s Day Card Evolved” by Marilyn Yalon, Feb 14, 2018. www.time.com/514173/valentine-card-heart-book/ (adapted with permission from The Amorous Heart: An Unconventional History of Love

- Museum vertical files

- “Valentines,” Worcester Historical Museum Digital Exhibit, https://worcesterhistorical.com/digital-exhibits/valentines/

- “Valentine’s Day Facts,” History.com Editors, updated Jan 24, 2022; original Jan 8, 2019, accessed Feb 1, 2022; www.history.com/topics/valentines-day/valentines-day-facts

- “Valentine’s Day Greeting Cards – Image Gallery Essay,” Wisconsin Historical Society, www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS3880

- “‘The Valentine has fallen upon evil days’: Mocking Victorian valentines and the ambivalent laughter of the carnivalesque,” Early Popular Visual Culture special issue: Social Control and Early Visual Culture (Vol. 12, Iss 2, 2014; p. 127-173), first published online August 21, 2014 https://cris.brighton.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/341390/EPVC+-+The+Valentine+has+Fallen+Upon+Evil+Days+-+for+repository.pdf

- A Very British Romance series, Lucy Worsley, 2015, BBC / PBS

- “Victorian-Era ‘Vinegar’ Valentines Could Be Mean and Hostile” by Crystal Ponti, Feb 10, 2020; www.history.com/news/victorian-valentines-day-cards-vinegar

- Vintage Valentine Museum blog/digital exhibit – Whitney, Carrington; http://www.vintagevalentinemuseum.com/

- “Whitney Made: The Man Behind a Valentine Empire,” Chad Sirois (Communications Manager), Worcester Historical Museum blog, https://www.worcesterhistory.org/blog/whitney/

- “Who Sent the First Valentine’s Day Cards?” Anna Attkisson, Business News Daily, updated Dec 21, 2021, www.businessnewsdaily.com/3951-first-valentine-cards.html

- Worcester Historical Museum Resource Guides – Howland Valentines, https://worcesterhistoryblog.files.wordpress.com/2020/04/howland-valentine-collection-2001.fia_.06.pdf