Victor Arland, founder of the townsite Arland, is somewhat of a local legend in Park County. For all the myths and legends surrounding him, there is very little historical documentation.

Arland was born in 1848 outside of Paris, France. One source reports that he lived in Vincennes, France. Vincennes, a commune on the outskirts of Paris, is located in the Île-de-France. As a young boy, Arland would have seen the region’s population grow fourfold, perhaps contributing to his decision to leave France in 1870 at the age of 22.

Arland arrived in New York, New York on July 13, 1870. His occupation is listed as “farmer.” Vincennes, with its fertile loam soil, was an agricultural hub next to Paris. It’s likely that he was involved in the agricultural industry before leaving France. It is also likely that this is where he first met his lifetime friend, Camille Pierre Dadant.

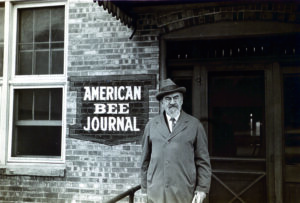

Photograph of Camille Dadant courtesy of Dadant & Sons Inc.

Camille Pierre Dadant left France in 1863. His father, Charles, was reportedly disillusioned with business opportunities in France and moved the family to Hamilton, Illinois with the intent to grow Champagne grapes and raise bees. While the grapes did not work out, the family established a beekeeping business that is still around today.

While the Museums were unable to find any documentation of a relationship in France between Arland and the Dadant family, Arland headed to Hancock County, Illinois as soon as he reached the United States. Hancock County happens to be where the town of Hamilton is located, where the Dadant family was expanding their beekeeping business. Additionally, on at least one occasion Arland’s brother wrote Camille Dadant to get ahold of him. As Victor’s brother remained in France, it suggests the families knew each other there.

In her brief biography of Arland, Carol Hunter writes that Arland, “had been in the business of shipping fruit and country produce to the city of Paris.” This business could have led Arland to meet the Dadant family, who were also in the agricultural business but living in Langres, France, almost 300 kilometers from Vincennes in the Champagne region.

The earliest correspondence housed at the McCracken Research Library between Camille and Arland is dated August 11, 1872. From Hamilton, Arland went south and, at the time of writing the letter, had been living in New Orleans and working at a restaurant. He wrote of his intention to head back to Illinois.

After a year with no preserved correspondence, letters in 1874 show that Arland was employed raising grapes in Grafton, Illinois. In a September 14, 1874 letter addressed to “Sir,” Arland stated his plan to travel to St. Louis for the fair before spending the winter in Colorado.

As editor of the American Bee Journal, Camille dedicated a page in the May 1925 edition to Arland. Dadant wrote:

“I had a friend, three years older than myself, who had arrived from Europe in 1870. He was a single man, athletic and fearless, but with a very pleasant, beardless face. He wanted activity. The lure of the Great West fascinated him. He took advantage of the gold excitement in the Black Hills, in 1875, to direct his steps in that quarter. But the Black Hills proved of little value and he went beyond. He was fond of hunting and spent a number of years on Trail Creek, Wyoming…” (224).

In May 1875, Arland wrote to Camille from the Spotted Tail Agency in Nebraska. Arland wrote that a party was preparing to go to the Black Hills for hunting as no big game could be found around the Agency. He wrote, “I like it quite well here, in spite of the fact that I could like it better in areas a bit more favored. One can’t run after adventure and stay at home at the same time. However, I don’t think I’ll remain very long in these wild areas.” Arland closed his letter saying, “Present my compliments and respects to all your family. I hope that now the bees are working well.”

By 1878, Arland was at Fort Custer, Montana and apparently tiring of his nomadic lifestyle. He wrote, “But I’ll tell you that I am beginning to get tired of this sort of life. Civilization is more agreeable than all the liberties that one enjoys in the solitary spaces of the Far West. I’ve decided to return home next spring.”

Arland’s return to France was postponed. Arland entered into business with John F. Corbett in 1880 and the partners established a trading post on Trail Creek, a tributary of the Shoshone River.

On March 1, 1882 from Trail Creek, Arland wrote Dadant, “I have been forced to postpone my return to France until further orders.” Arland, seeing an opportunity for profit, built a ranch on Trail Creek. The construction of the ranch cost Arland $200; today that would be approximately $5,668. Arland sold the ranch to fellow Frenchman, Count Ivan du Dore for a $400 profit. With the ranch sold, he wrote that the business venture with Corbett was what kept him in Wyoming: “Since the little business promises to do well, I am going to remain here for some time yet, perhaps a year or two.”

It was at this trading post that Arland began to order honey from Dandant & Son. Camille Dadant wrote, “In 1882, having received one of our honey price lists, he ordered 1,000 pounds of honey, in pails of 25, 10, and 5 pounds, to be sent by freight to Billings, Montana, 140 miles from him.”

Arland believed, “I could easily sell 2 or 3 barrels of honey. The Count du Dore would take one barrel for himself alone. Please tell me in your answer what your prices are, and what the cost of shipping as far as Coulsen would be. If the prices were satisfactory, I would take not less than 1,000 lbs.”

The railroad, still being built to Billings by the Northern Pacific, was finished on August 22, 1882. Just two days before the completion of the rail, Arland wrote Dadant, “Now it will no doubt be impossible to do business together before next spring; the railroad not being terminated, as one had reason to hope, last spring.” Despite the delay, Arland had been busy acquiring customers and listed several men who would buy honey and wine. By October, Arland placed his order for honey including 20 pails of 25 pounds, 26 pails of 10 pounds, and 48 pails of 5 pounds. The wine order was delayed until spring.

During his time at Trail Creek, Arland was busy farming. In his October 18th letter to Dadant, Arland writes, “Now I have a piece of news of the greatest importance (for me!) to tell you. Guess!!! We have harvested 6,000 lbs. of potatoes, 600 lbs. of onions, without counting a large number of cabbages, carrots, and other vegetables. What do you think of that! And so, we are really enjoying ourselves. If you had been several years without eating any vegetables, you would understand that well.”

It seems that despite living in the West, Arland continued to be involved with agriculture and even took great pleasure in it. Hunting, however, had to be put aside. On April 18, 1883, Arland wrote, “I am announcing to you that I have put hunting aside, for my present business leaves me scarcely enough time to furnish the house with game. But each time the chance to kill a bear comes, I don’t miss it, for I have no sympathy for those animals.”

Up until this point, there was no bridge across the Shoshone River, then referred to as the Stinking Water. This made travel to and from Billings, where Arland conducted most of his business, unpredictable and treacherous. Others in the Bighorn Basin were similarly affected. In March 1883, Congress had authorized a mail route from Billings to the Stinking Water. In July, as a response to the route, Arland and Corbett moved their trading post at Trail Creek. Arland wrote, “We are going to move our store close to the bridge, about 10 miles from our present location, which will increase our business considerably.”

Unfortunately, no progress was made on the route until 1884. Despite the slow pace, the move of the trading post was a wise decision. In December 1883, Arland wrote, “Since we have been established at Cottonwood, our business has increased considerably; for we are on the road from Camp Brown to Billings.”

Despite the success of their newly-located trading post, in March 1884, Arland announced a new business venture to Dadant, “We are going to build a new store on the Meeteetse, about 35 miles to the south, and in the center of the cattle raisers of this area … We are going to sell our place on Cottonwood to a cattle raiser; it is a good location for that purpose.”

At their new location, the business partners built a store, clubroom, and restaurant. Amidst the building project, Arland continued his agricultural pursuits: “Crops such as potatoes and oats are uncertain because of the frosts in the month of August. Its vegetation is tardy; this year the trees grew their leaves only in the first days of June. I planted some potatoes, as a try, in the last days of May.”

By October, Arland wrote Dadant that after a cost of between $1200 and $1500, the building of “Vicksburg” was nearing completion, but it had taken a toll on him: “My health leaves something to be desired, at the moment, but since in 2 or 3 weeks our buildings will be finished, I will take a little rest, which I greatly need. For it is necessary that I direct the outdoor work and do the counter work while J. Corbett is on the road to Billings. Thus I am forced to spend a large part of each night serving the clients, which is very fatiguing, I can assure you.”

While the townsite is remembered as a wild place – with shootings, gamblings, and brothels – in December 1884, Arland was proud that his town was none of those things. He wrote Dadant,

In the towns of the Far West [cowboys] are getting a most deplorable reputation through their audacity and lack of restraint. But at our place, I can assure you, they behave very well, which astonishes very much those who don’t know cowboys thoroughly. In the early days, when I first kept a saloon, they thought that I would permit them all liberty at our place; but after having thrown into the river several of these desperate characters, they showed lots of respect for us and our place.

Throwing rowdy cowboys into the river may have had something to do with Arland’s poor health in 1884. A rough winter meant that Arland did not get the respite he had hoped and honey sales were poor, but by spring Arland was feeling recovered and a good summer caused business to pick up for Arland and Corbett.

Despite success in business, Arland seems to continue to be homesick for old friends and France. He writes Dadant, “I hope I will be in a position to go pay you a visit next year; and if, by any chance, I were capable of inspiring a ‘tender passion’ in the heart of a Frenchwoman of 25-30 years of age, I would be happy to make her my life companion; for I believe more and more that it is not good for man to be always alone.” Arland’s belief might have had something to do with running a saloon.

Dadant, who had been married since 1875, seemed to have played matchmaker on his end for in the next, November, letter, Arland wrote, “Please pay my compliments to the French ladies who are interested in me, and particularly to those who are personally interested in me.” With a hard winter in 1886-1887, Arland likely had little time to think about France (and French women).

In a letter from Arland’s brother in Varennes, France dated January 1888, Arland’s brother appealed to Dadant for news of Victor Arland. Arland’s brother wrote, “Please, I beg you, have the kindness to give me some news of him. He wrote me in April, telling me that he had almost been assassinated and that his health wasn’t too good at that time.”

The Museums were unable to find newspaper articles from that time mentioning an assassination attempt in April 1887 and Arland’s April 24, 1887 correspondence to Dadant only mentioned that though business was slow, he was busy, but he would try to finally visit Dadant soon.

Commotion did occur in early May 1887 when James Meenen shot Al Durant outside the Arland store. Durant survived five days before dying at a mail camp, three days after being shot. What Arland thought of the event is a mystery – his correspondence to Camille Dadant pre-dated the event, April 24, 1887, and post-dates it, July 6, 1887. The July letter only remarked on the honey received from Dadant and that Arland’s health was quite good at the moment, despite being overworked.

Almost a year later, Arland once again made headlines in the local newspapers. On March 1, 1888, The Fremont Clipper published the article “Killed in a Drunken Carousal.” The article stated, “Vic Arland shot and killed a man, known here as Scarface Jackson, and Arland P.O.” Scarface Jackson’s real name was D.C. Dye. According to The Enterprise, “Dye’s violent death excites no surprise, as he has frequently been an actor in gun fights of a less tragical termination.”

According to the paper, Dye was a jealous man with a wife who was fond of admiration. The couple had a ranch near Arland, ran a restaurant, and Dye was employed by Otto Franc at the time. The paper stated, “The day before the encounter Dye had a fight at Arland’s place with some Lothario, whose name was not learned, and it was on Dye’s return from his ranch, armed with a deadly Winchester to take revenge on his adversary, that Arland interposed to prevent a breach of the peace and had to kill his man to do it.” At the time of Dye’s death, Arland was hosting a dance with an attendance of almost 50 people.

This time, we do know what Arland thought of the event thanks to a letter sent to Dadant on March 12, 1888. Arland wrote, “I was obliged to kill a man in order to avoid being killed myself. Immediately I sent for the Justice of the Peace, who came to the scene, investigated the whole affair, and convoked a jury which rendered the verdict of justifiable homicide.”

“Shoot or be shot” could have been Arland’s motto as he went on to mention two previous attempted assassinations, including the one referenced in the letter from his brother to Dadant in January 1888.

Of the first attempt, Arland wrote, “I must tell you that twice I’ve been attacked by these ‘bad men,’ and that it is only through my agility and cool-headedness that I escaped being assassinated. The first one, a man named Joe Crow, a horse trainer, a violent and hot-headed character, behaved in such a manner that I was obliged to tell him to quiet down. He answered me with a revolver shot and took flight without waiting for any answer…” Arland claimed that Joe became sorry for attempting to shoot him and, after Arland forgave him, “that man would have died for me.”

In the second attempt, a man by the name of Thomas Brady was still aiming his revolver at Arland when Arland shot him first. Perhaps Brady and Arland had a disagreement over New England’s virtues. Arland concluded, “So you see, there are more thorns than roses in life in the Far West.”

Arland’s case was taken to Lander where Arland was acquitted. Arland wrote of the verdict, “I came out of this affair with honor and consideration.”

Despite having the law on his side, with so many shootings, you might conclude that Arland was the problem. However, The Enterprise, in the announcement of Dye’s death, stated, “Arland kept a store at the crossing of the Stinking Water, and is a merry, active Frechmen [sic], well respected and of a peaceable disposition.”

At the beginning of October, Arland fired an unnamed employee for his habit of drinking. With the loss of the employee, Arland was short-handed and unable to visit Dadant, something which appeared to take a toll on Arland who wrote that he was tiring himself too much at the business. His overexertion seems to have taken a physical toll. At the end of the month, Arland wrote Dadant after returning from Billings where he had been recovering from a fever that lasted the whole summer.

Arland might have been overdoing it at work, but he was also still without his dearest friends and family. In this October 26 letter Arland wrote, “I found your picture and your father’s, for which I thank you very much; for it pleases me to receive the likenesses of those whom I hold dear.”

In February, Arland announced his decision to sell his business. He wrote, “I hope to be able to go see you this year, for I have made the resolution to sell my place this year, if I find a reasonable price for it. I must tell you that this store life fatigues me a bit too much, and I am forced to take up a life of activity.” Several months later, in June, Arland wrote again of his intention to sell:

I intend to liquidate my business this year, for my health leaves something to be desired, and it is impossible for me to go away for several months, as I had at first intended. If I do succeed in selling, my first visit will be for you.

I must tell you that life in the great West tires one out enormously, and I have had enough of it for the present.

In September, Arland wrote that once more he would have to wait to sell his business as the value of everything had decreased across the nation. The delay meant he would not be able to return to France, but he still hoped to visit Dadant that winter.

On April 24, 1890, Arland was in Red Lodge, Montana with friends at John Dunnivin’s saloon when he was shot and killed by someone standing outside the building. The Wyoming Weekly Republican connected Arland’s death to revenge by William Landon for the death of his friend, Jackson (whose real name was D.C. Dye). Immediately after Arland’s death, “Deputy Sheriff Frank Bellar, at the instigation of Dyer and Wilson, arrested a man by the name of William Landon, on suspicion. It seems that this man was arrested on the grounds that he and the deceased had some trouble in Wyoming more than a year ago, and were considered bitter enemies.”

Samuel “Lum” Wilson, one of Arland’s friends and one of the men who insisted on the arrest of Landon, was later a man of the law himself in Missouri. He was known as a well-respected, dependable, and upstanding member of society for many years there. Despite the arrest, William Landon was later released as there was not enough evidence to hold him.

John Corbett, Arland’s business partner, wrote Dadant of Arland’s untimely death at the age of 42. Almost thirty five years later, Dadant wrote of the partnership, “Corbett and Arland were very devoted to each other, having saved one another’s life several times.”

Arland was never able to return to France where his sister, brother, and their families lived and he never did get to see his dear friend Dadant again. Arland died in the West that had once enchanted him and then exhausted him.

There are several myths and legends about Arland, including one that he had buried his gold in the area surrounding the town of Arland. This seems unlikely, given the number of times Arland wrote to Dadant, a lifelong friend, to apologize for late or partial payments. Arland was also rumored to be a ladies man, but none of the sources from his time mention this and his only mention about ladies is in reference to the idea of a Frenchwoman he could settle down with eventually. Arland may have been a difficult man to be around at times, something he himself acknowledged, but Arland’s story may be a case where fact is less enchanting then legend.