Bison of the Bighorn Basin Project: An Update

By Amy Phillips

Bison are iconic figures here in the West. Not only are bison the national mammal of the United States, they also have a rich history. To uncover some of that history, the Meeteetse Museums embarked on the “Bison of the Bighorn Basin” project in September 2020. The project, originally set to take place during September is currently on-going. To date, staff have measured 82 bison crania from 64 individuals and three institutions. A special thanks to the Worland Museum and Cultural Center, Homesteader Museum, Old Trail Town, and the Bighorn Canyon National Recreation Area for welcoming our staff during the project.

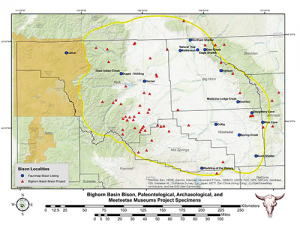

This map shows archaeology sites with bison remains (blue) and the bison crania measured during the project with known location information (red).

“Cranium” (plural “crania”) refers to the skull without the lower jaw (mandible). Crania are a reservoir of information, encoding information on diet, environment, sexual dimorphism, where the animal lived and when. Much of this information is not readily apparent at first glance but is hidden in metric measurements and more advanced sampling. Within the Bighorn Basin, much of the bison material found in archaeological sites is post-cranial (see map). By focusing on the crania, the Museum is documenting information that was already part of the landscape and can result in new information about this regional population.

Staff who conducted the program were trained by Dr. Lawrence Todd, Professor Emeritus in Anthropology at Colorado State University, to take a total of twenty-six measurements.

Staff takes measurement SK2, the horn spread at its widest point.

Because of the nature of preservation, the crania brought in by the public likely would not be complete, reducing the possible number of measurements that could be collected.

As expected, most crania brought in were male. Male or bull crania are more robust, a feature which makes them more attractive for decoration and therefore more likely to be removed from the landscape.

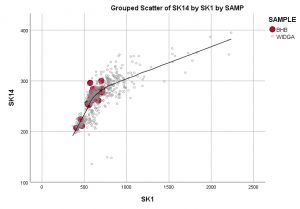

Comparing the Bighorn Basin bison with a national dataset gathered by Dr. Chris Widga, head curator at the Gray Fossil Site in Eastern Tennessee, revealed that the Bighorn Basin bison were the same size as modern bison. Modern bison morphology, or size, first appeared about 3,000 years ago. In other words, when bison reached their current size, England was in the Late Bronze Age, the Phoenician alphabet was spreading through the Mediterranean, and humans had been in North American for about 10,000 years.

Bison from the Bighorn Basin Project (red) compared with the bison in Dr. Chris Widga’s national dataset (grey). The results show that bison are morphologically modern.

These modern bison were the most recent “installation” of much larger bison such as Bison occidentalis, Bison antiquus, Bison latifrons, and Bison priscus. These older and larger bison were megafauna much like mammoths and mastodons. They were as much as 25 to 50 percent larger than the bison today and some had horn core spreads of as much as six feet.

The bison measured in our study were then put through a semi-log plot to estimate age at death. The plot was developed by Michael Wilson and has been used by Danny Walker and Dr. Kenneth Cannon. It soon became apparent further testing was needed for the accuracy of the semi-log plot. Not only was there no way to estimate the age of modern female bison, but the plot would not estimate bison with a SK14 measurement over 280 mm. To refine this model, the Meeteetse Museums is working with Sam May of the nearby Antlers Ranch to measure bison of known ages and sex (both male and female). This information will be added to prehistoric (or fossil) bison. The hope is that the additional measurements will refine the semi-log plot and increase the accuracy of estimating age.

Bison specimen 105 marked with the SK1 and SK14 measurements used for both the morphology comparison (above) and the semi-log plot (below). Bison 105 was female, and age at death could not be estimated using the semi-log plot.

Semi-log plot for bison specimen 104. Notice the model does not have a line for “Modern Female” bison.

Today the project continues. A podcast season discussing the story of bison will be released soon everywhere you get your podcasts on “Meeteetse Stories” (including Apple Podcast, Spotify, Stitcher, and Podcasts.com). The podcast season will feature historic accounts of bison in the Bighorn Basin and interviews with bison experts from archaeologists and paleontologists to wildlife biologists. Additionally, staff plan on creating an exhibit focused on the project and history of bison in the area.

The project is far from complete and more testing on the bison themselves is needed to truly understand the dataset collected.

The biggest unknown today is when the bison in the project lived. Staff are currently seeking funding to date some of the bison in the project. Radiocarbon dating costs roughly $310 for each bison specimen. Testing all 82 bison crania is not feasible as it would require the Museum to find over $24,800 in funding. As a result, testing on the bison will work based on location information. The more complete the bison’s location of “finding,” the more likely it is for the Museum to perform further testing on it. While this does limit the information project participants can learn about their specific crania, it allows us to learn more about bison in the region as a whole. Since bison are herd animals, their responses to climatic events, forage quality, human hunting, and more will be similar.

As mentioned earlier, crania also contain information about the environment in which the animal lived. Stable isotope analysis can give us an idea of what the bison ate and where they ate it. Carbon isotopes determine whether the animal ate primarily C3 or C4 plants. C3 plants represent the majority of plants (including many plants in cold and temperate climates, like ours). C4 plants are warm weather plants. Analysis of C3 and C4 in the animals can tell us about the environment in which they were feeding. Strontium isotope ratios are used to gain information about movement. Like C3 and C4, strontium is incorporated into the body via diet. (For more on carbon isotope analysis, see Dr. Ken Cannon’s dissertation or view his 2020 presentation for the Meeteetse Museums). Strontium ratios in soil, rocks, and water vary greatly from place to place. So, strontium can tell us where the foods the animal was eating originated. Since bison are grazers, the strontium rations recorded in their teeth tell us where they were eating, which reflects their movements. (To learn more about how strontium isotopes are used with bison, see Dr. Chris Widga’s paper on Middle Holoccene Bison). This strontium analysis is conducted on the teeth and involves an extra cost.

Finally, bison were nearly wiped out from over-exploitation in the 19th century. The North American bison population fell from an estimated 30 to 60 million to just 300. With that bottle-necking event, DNA material was likely lost. Without testing DNA from bison in the archaeological record, there is no way to know how much diversity was lost and, consequently, how that might impact bison today and in the future. DNA testing of the bison from the Bighorn Basin project can provide important information for wildlife management today.

To donate to the project, visit “Donate” on the upper right hand of the Meeteetse Museums’ website and choose the “Bison of the Bighorn Basin Project” or call (307) 868-2423. For more information, email programs@meeteetsemuseums.org.

[…] Bison of the Bighorn Basin Project: An Update […]